31 December 2025 / 1 January 2026

May this bell dispel

the delusions of all beings

everywhere.

Today, as we ring out the old year with the joya no kane ceremony, we are reminded that we live in a dream. The dream of the past, the dream of memory, the dream of attachments, the dream of success, the dream of failure, the dream of the future. Only in the present moment are we awake.

Thus we ring the bell on New Year’s Eve to dispel the 108 bonnos to clear our heads and hearts of the delusions of this year so that we can make room for the emptiness of the new year, with all its promise and potential. But as the second of the Four Great Vows reminds us, “Delusions are endless; we vow to drop them all.”

In the ordination ceremony we chant the Confession Sutra, the San Ge Mon, which lets us imagine that we can put aside a lifetime of past mistakes and misdeeds, which were the result of the three poisons—Greed, Anger, and Ignorance—and are the inexhaustible source of all delusion. We vow to consecrate our body, mind, and words to follow the true Way of Zen.

Of course these rituals are symbolic; they are not magic spells. We are still subject to the laws of gravity; still prey to greed, anger, and ignorance; still entangled in karma. But these rituals can be even more meaningful for this reason, and the results can be miraculous.

This year’s bell ceremony is particularly meaningful to me.

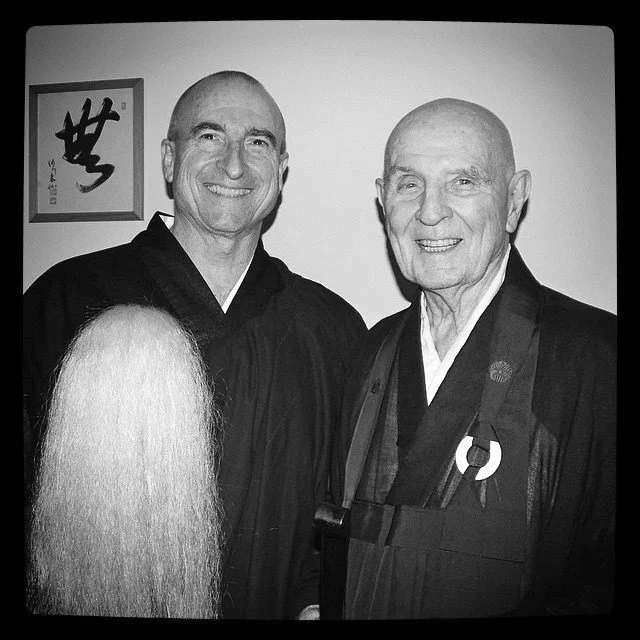

Ten years ago, at midnight, as 2015 turned into 2016, Robert Livingston Roshi met me in the dojo of the New Orleans Zen Temple, just him and me, for the intimate shiho ceremony, in which the teacher acknowledges the student’s transmission. Robert handed over his kotsu, the simple spinal-curved stick with the purple cord and tassel that is the symbol of the Zen teacher’s authority.

“But you will need your kotsu,” I said.

“Why?” he replied. “You are the abbot now.”

Robert was not one to hand over his authority lightly. In the past when he tried to do so, he soon took it back. Yet now he bestowed it with an alacrity that did not accord with the weight of responsibility that I felt fall on my shoulders. His retirement was complete.

As 2025 is about to turn into 2026, I look back and see how much has changed in a decade. Mujo, constant change, impermanence, is a key teaching in our practice. Yet it is always surprising how little we are prepared for it.

For the five years that followed receiving shiho, I took care of Robert and the temple until his death in the early morning of January 2, 2021. Since then, the temple no longer occupies 748 Camp Street, where it had been for thirty years. Now the temple has two locations, one in the bend of the Mississippi River in New Orleans, and the other high on the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. Muhozan Kozenji (Peakless Mountain Shoreless River Temple) is no longer a metaphor.

Our sangha has changed its appearance as well. We lost many of the old-timers who were uncomfortable with the transition to a new abbot and new surroundings. Change is difficult. But although the people come and go, the practice remains the same.

During the decade, hundreds of newcomers have passed through our dojos, some serious, some curious. I have ordained some 25 lay practitioners, a dozen monks, and two new teachers who have their own dojos.

We remain a sangha with a distinct flavor, a certain character, one that attracts highly independent individuals unafraid of discipline but suspicious of any organized religion, including this one. As someone from another sangha once said, not entirely inaccurately, “At NOZT they throw cubs off the cliff to see if they survive.”

Some things have not changed. We still practice zazen. We still hold introductions to Zen practice. We still have zazenkai and sesshin. We still chant the Hannya Shingyo, the Four Great Vows of the Bodhisattva, and the lineage in Japanese. Though our sangha is still small, our practice is vast. For it is none other than the authentic practice that Robert Livingston inherited from Taisen Deshimaru in the early 1980s and brought here from France.

Ten years from now, who knows what changes might be in store for us. I don’t know, but I suspect that we will still find a way—whether I am here or not—to continue to offer a place for those with the discipline and vision to follow the Way of Zen, which, as Deshimaru told his European students as he bid them farewell for the last time on his way to Tokyo where he died, is simply to do zazen éternellement, until we die.

Richard Reishin Collins and Robert Reibin Livingston, January 1, 2016, New Orleans Zen Temple