Richard Reishin Collins

Spring “Cicada” Sesshin, 24-26 May 2024

Stone Nest Dojo, Sewanee

The Spring Sesshin at Stone Nest Dojo of Sewanee Zen took place near the end of May, with a small group of practitioners, some who had practiced some ten or twenty years, some fewer, and one who had never practiced zazen at all. Over the course of three days of intimate and intense practice, sitting, working, and eating together, the Abbot gave a series of kusen (talks during zazen) on Sekito’s “Song of the Grass-Roof Hut.” This is a transcription of the talks that were recorded and a reconstruction of those that were not recorded. Each sitting of zazen seemed to have its own musical accompaniment, whether it was the booming percussion section of a severe thunderstorm in the morning, a symphony of cicadas in the afternoon, or a double-bass ensemble of frogs at night. This accompaniment may or may not have been captured and echoed in the tone of the talks themselves.

KUSEN ON THE POEM

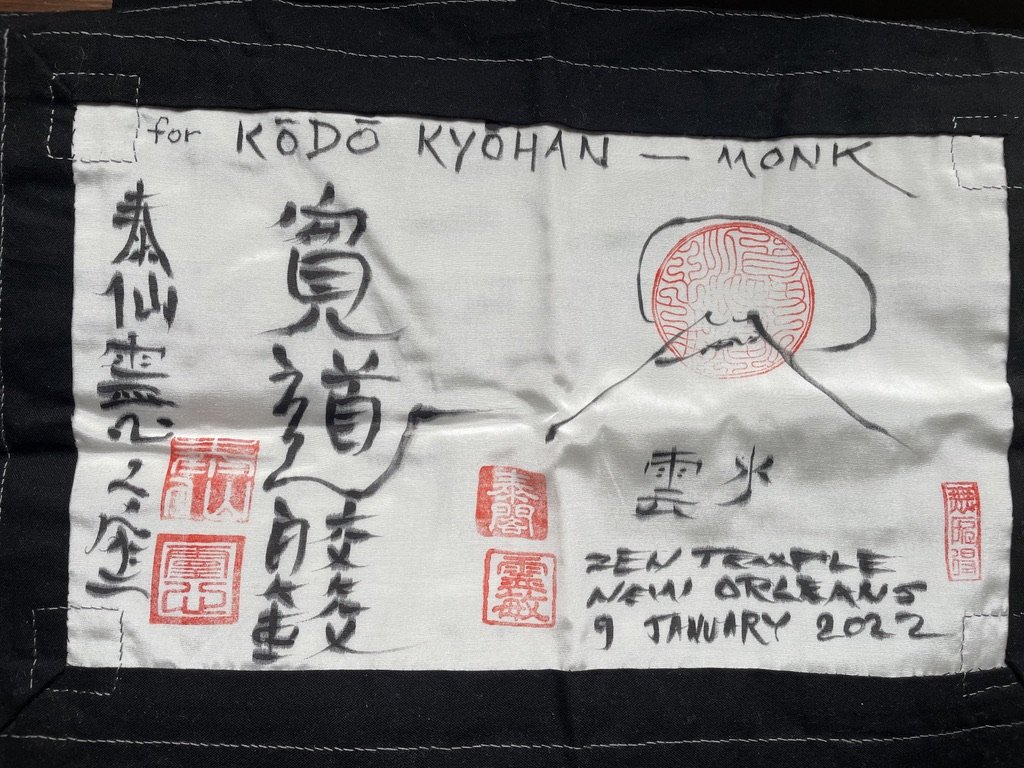

Sekito (or Shitou in Chinese) was known as “Stone Head Monk” because he would practice zazen on top of a great flat rock in the Heng Mountains of China. Sekito’s master was Seigen, and Seigen’s master was Eno, the Sixth Patriarch. Several sesshin ago, I focused on another of Sekito’s classic Zen poems, the Sandokai, which I adapted for my master, Robert Reibin Livingston Roshi, on the occasion of my shiho in 2016, since that poem is all about the meaning of transmission. This sesshin I would like to focus on Sekito’s poem “Song of the Grass-Roof Hut,” in part because I have been translating Philippe Coupey’s commentary on it, and in part because this new dojo, where we now practice, has only been open for a year, and although its name is Stone Nest, which sounds permanent, it too is really just a temporary grass hut.

I’ve built a hut with a thatched roof, which houses nothing of value.

A dojo is a place where nothing of value is stored. Of course we have our instruments and statues and zafus, but really none of this is essential. Its emptiness is its value.

After eating, I relax and take a nap.

Simple. This is Zen practice. We tend to complicate our practice with philosophical discussions and hypothetical ethical questions, but this is really all there is to it. As Coupey points out in his commentary, we even complicate something as simple as eating, with whole conferences dedicated to discussing what Zen practitioners should or should not eat. Yet Dogen said simply, “Eat soberly.” And Deshimaru said, “Sometimes I eat meat, sometimes I don’t.” Traditionally, monks are meant to eat whatever is given to them. The only food to avoid eating is preferences. Eat. Relax. Take a nap.

As soon as the hut was finished, new growth sprouted.

Now that it has been lived in, weeds cover it all.

The emptiness of the hut creates form, its form creates emptiness. The exterior form of the hut attracts more form, phenomena. Ku becomes shiki, the inside shapes the outside, and vice versa. Life lived creates karma. It is unavoidable. And as much as we might prefer to have only grass or only flowers, weeds too will sprout and proliferate. But weeds don’t matter. Flowers don’t matter. Only the indiscriminate emptiness of the hut matters. The hut where we cut karma.

The man in the hut lives here peacefully

Without attachments inside or outside.

The attachments that the man in the hut has let go of include everything superfluous, most material possessions, but also intangible things, like ideas, ideals, concepts, preconceptions, even the precepts themselves, even Buddhism, even Buddha. Nothing on the inside, nothing on the outside. Nothing to obstruct his practice of the Way.

He does not desire to live where ordinary people live.

He does not desire what ordinary people desire.

Desire, of course, is itself the culprit, the source of our suffering. But this “ordinary people” or “common people” is an interesting term. As Coupey points out, many translations (he says “American” translations) avoid using the term “ordinary people” because it can seem elitist or condescending, as though Sekito were speaking from a superior, elitist vantage point. And in a sense he is. But “ordinary or common people” are not the opposite of superior people but rather the opposite of those who are not subject to the common or ordinary desires. By ordinary people, Sekito is not referring to poor people or workers but rather to those who think they are superior or can become superior or satisfied or happy by reason of their current or aspirational social or economic status. Ordinary people are people who value social status, honors, awards, titles. They are attached to these superfluities, and when these illusions go up in a puff of smoke, so does their self-esteem and their raison d’être. Most of us live more or less like ordinary people, at least in material terms, since we live in houses, pay bills, drive cars or ride bicycles, scroll on our phones, just as Sekito’s mountain monk has a zafu, cookware, ink and brushes, and so on. The key is not to become attached to these necessities, not to be owned by what we own. Sekito is interested in the man who lives in the grass hut peacefully, without regard for what he owns or how he is seen in the world, who is what Rinzai called “the man of no rank.” The man of no rank has no wish to add to his resume. Nor to his possessions. He has no need to build a house in a good neighborhood with curb appeal for the passersby. Why? Because he knows:

Although it is tiny, this hut contains the universe.

One practices not for oneself, not to fulfill one’s own desires, nor the desires that others have for us, but for all existences. No gilded palace or capacious monastery can hold more than that, just as the layman Vimalakirti’s house contained vastness. And to contract the universe even further, within the hut is an even smaller space, the square meter of space where the man of peace sits on his zafu.

In one square meter, an old man clarifies things and their essence.

In other words, he sits in zazen and allows forms to come and go in the parade of mutability which he observes without being disturbed or distressed by it. This clarifies what might seem muddy, calms what might seem turbulent to the ordinary or common man. Sekito himself was such a man of zazen. When he died, he was supposedly mummified in the lotus posture, and perhaps you can still see him at Sojiji temple in Japan. So now the Stone Head Monk of the mountain (if those are really his remains) finds himself sitting in the midst of the big city of Yokohama. Whether this is Sekito or another monk who took his place after being rescued during the Sino-Japanese War or stolen by Japanese troops during the Second World War hardly matters. What is clear is that no abode is permanent, not a hut, not a temple, not a body, not even a grave.

The Mahayana bodhisattva has absolute faith.

Ordinary people can’t understand, their doubt never ends.

Unlike the Hiniyana arhat who clarifies things for himself as a model for and representative of others, the bodhisattva of the Mahayana tradition goes beyond the five skanda (those aggregations of early Buddhist philosophy that constitute proof of our existence) to add the dimension of emptiness out of which come the five skanda and upon which they depend for their own existence. Here again, ordinary people are mentioned in contrast to the bodhisattva, but these include even the practitioners who practice only for their own enlightenment, those who are not interested in awakening or who are interested only in their own awakening, versus the bodhisattva who is interested in the awakening of all beings. And since the doubt of ordinary people never ends, so does their suffering. Their questioning questing continues:

Will this hut last or not?

Perishable or not, the original master is here

And resides neither north nor south, east nor west.

Where then does the “original master” reside if not in the four directions? He resides here and now, at the very intersection of left and right, up and down, past and present. And who is he? The original master is the self we have not yet thought of (to paraphrase Kodo Sawaki), the one who has our face before our parents were born, the one that persists in each of us and is shared by all the patriarchs of the past and future, and yes even the Buddha, but also Bodhidharma and Eno and Sekito, and us. Does it then matter if the hut lasts or not? And since we are the hut, we know the answer to that. However,

So firmly rooted, he can’t be surpassed.

Firmly rooted in the practice of zazen, how can the man of no rank be beaten since he is hors de combat, having left the struggle, having dropped out of competition? He is not subject to threats or bribes, having no fear of loss, having no desire of gain.

A bright window among the green pines puts

Jade palaces and gilded towers to shame.

In what Coupey calls the American versions of the poem, the hut and palaces “cannot be compared,” but I would like to stress that the unadorned and unpretentious hut, in the beauty of its simplicity, like the plain man of no rank, cannot be surpassed by ornate edifices, and thus “puts them to shame.”

Sitting with his head covered, everything becomes peaceful.

Simple. Concrete. Practical. When hungry, he eats. When tired, he sleeps. When cold, he covers his head with his kesa. And in so doing, meeting needs as they arise, he can be at peace, here and now. There are, of course, many depictions of Bodhidharma (Daruma in Japanese) sitting in zazen with his robe covering his head. Here is the original master invoked again.

This mountain monk grasps nothing.

This mountain monk is Sekito, Daruma, Buddha, anyone who takes the posture. But only if, during zazen, they grasp nothing. I use the word “grasp” and deliberately avoid the more abstract “understand” for its greater combination of concrete and connotative meanings: grasping for meaning, grasping at concepts but also grasping onto things, whereas understanding has lost its connotative imagery of “standing under” something and means merely to comprehend (which at its Latin root, however, almost retains the sense of grasping, com = together + prehendere = grasp). And again, such grasping can have as its object either material or spiritual goals. But this mountain monk grasps at nothing, even his own liberation.

He lives here and no longer strives for his liberation.

Coupey invokes the last few frames of the Oxherding Pictures, where the seeker has already glimpsed, caught, mounted, and tamed the Ox, and has now internalized the Ox so that he can sit peacefully without further goal. He no longer needs to know. Grasping nothing, he is content with the balanced mental state of “just don’t know” or “knowing not knowing” which is not unlike Dogen’s “thinking not thinking” or hishiryo consciousness.

Who, out of pride, would want to attract students with a place to sit?

How many Zen students succeed in dropping the desires of ordinary people, and practicing diligently and peacefully, only to have the pride of ambition arise with the desire to become a Zen teacher? They should be careful what they ask for. In the shuso ceremony, in which a student becomes a student-teacher, he is asked what he will do with the shippei, a symbol of the teacher’s power, which can be used for life or for death. It is an awesome responsibility, one that pride alone will not sustain. Most students are better off not becoming a teacher at all, Sekito implies, but focusing instead on their own practice.

Turn your light inward, please, and return to yourself.

What self are we talking about? Not the little ego of me-me-me, certainly. Not the self of the ordinary or common person, which is formed and thus limited by its environment and upbringing. But rather the self of the original master, the one we have not yet met, the one that is, though, always available.

The source is infinite and inconceivable, we can neither face it nor turn away.

The source or origin is within us always, and yet it can never be fully revealed, whether we come face to face with it or not. As Dogen said, “to study the Way of the Buddha is to study the self, to study the self is to forget the self, to forget the self is to study the self, and to forget the self is to be affirmed by all existences.” And so there is only one thing to do:

Meet the masters of old, become intimate with their teachings.

To meet the ancient masters cannot be done in the ordinary way by seeking them out and shaking hands. To become intimate with their teachings is not simply to read them or even to study their writing deeply. Like Dogen, we must study their teachings by studying the self, and to study the ancient masters is to forget the ancient masters; to forget the ancient masters is to study them intimately through our own practice, and thus to practice the Buddha Way. Sometimes when I am chanting the Hannya Shingyo, I can hear not my own voice but that of Taisen Deshimaru, and through Deshimaru, all of the ancestors in the lineage backward and forward in time. To become intimate with what the old masters taught is simply to become intimate with yourself. Because “when the mind rests on nothing, true mind arises.”

Knot the grass to build the hut and don’t abandon it.

The work is not intellectual but physical and spiritual. Doing the work of building the hut means securing a site where emptiness can be explored. A hut yes, but our body is our empty hut. And once we have established that practice place, which is what dojo means literally (“the place where we practice the Way”), we should not abandon it. We should not give up, but rather practice “eternellement,” as Deshimaru instructed his disciples when he left Paris to die. Eternally does not mean forever, and it does not mean that our physical site of practice will last for all time; on the contrary, the physical site of our practice is as impermanent as everything else; it is the spirit of our practice that is eternally in the here and now.

Let the centuries pass and let go completely.

It is up to you. Don’t simply observe the passing of time but drop all notions of time and space; this is letting go completely. Complete nonattachment, with nothing of value inside or outside. At the time of the Buddha, it was normal for monks to live in temporary huts like the one in the poem. Coupey tells the story of the monk, though, who wanted a more permanent place to practice, and built one of earth instead of grass. When the Buddha discovered this, he had it torn down to teach the monk an important lesson. You cannot build ku out of bricks. You cannot make a mirror by polishing a tile.

I opened my first dojo in Algiers Point in New Orleans, the second oldest neighborhood in New Orleans, just across the river from the French Quarter, on August 27th, 2005. As I finished the introduction just after noon, I learned that there was a big storm in the Gulf of Mexico. I proceeded to board up the windows of the dojo, packed up my wife and daughters in the car, and headed out of town just after midnight, expecting to be gone for a few days. Instead we were gone for a few months because August 29th was the day Katrina blew into town. A week or so after we left, I spent my 53rd birthday in Venice Beach, California. I remember building sandcastles with my younger daughter Isabel, who was only three at the time. And as the waves washed our work away, I realized that I still didn’t know if the dojo I had just opened had been washed away as well. Mujo, impermanence, constant change.

The grass hut is like the sandcastle, made to be washed away, a perishable abode, a temporary temple. Just like our dojo, just like the temple in New Orleans, which was supposed to last forever, but which we had to sell in 2022, some thirty years after it opened. Because a temple is not a building. Muhozan Kozenji, Peakless Mountain Shoreless River Temple, is not made of bricks and cypress and slate but of backbones, and knees pressing the earth, and heads pressing the sky. Home is where you hang your hat; a temple is wherever you place your zafu.

Open your hands and walk, innocent.

It is a matter of generosity, of not grasping, of opening the hand of thought, as Uchiyama put it, to allow all ideas of certainty and doubt to flow through our fingers like sand. Only in this way, by just knowing not knowing, can we be as innocent as a child in a bright new world, practicing with the spontaneity of clear awareness, naturally, automatically, unconsciously.

Thousands of words, an infinity of ideas, exist only for you

To free yourself from attachments.

Words are helpful, ideas are useful, but only if they are used like ladders that can be left behind once you have climbed to a higher altitude. If you cling to the ladder, how can you explore the mountain you have climbed to?

If you want to meet the immortal in the hut,

Please, here and now, don’t forsake the skin-bag that is you.

Some translations convert "immortal” into the “undying person.” But this is a literalization that obscures the allusion to Zen’s Daoist roots. Each tradition has its version of the wise or enlightened person. Confucianism has its sages, Theravada has its arhats, Mahayana has its bodhisattvas, and Daoism has its immortals.

The immortal is the teacher, but the teacher is not to be met outside of yourself. Even when you meet one of the immortals, one of the “original masters,” and you become intimate with them, i shin den shin, heart-mind to heart-mind, it is less a meeting in the physical world than a meeting of true mind. But don’t forget that at bottom we are all just sacks of blood and guts, and don’t forsake this vehicle of wisdom, the skin-bag that is you.

I have added “that is you” to bring home the message that this skin-bag refers not to people in general but to you specifically. This is important because unless we take the teachings to heart and become intimate with the fact of our mortality, we have missed the point of Zen. Name-calling, or malediction, is one traditional way to get the attention of monks and to take the teachings to heart, and to prevent them from, as my master said, getting big heads. Hakuin used to call prideful monks “shave-pate do-nothings.” Remember, we are all fragile containers of skin that can leak if punctured, just as our egos can burst when pricked, which is one of the methods a master might use to get this point across. Zen is nothing less than an existential crisis, a crisis brought on, faced, faced down, and gone beyond.

Sesshin means “to touch the mind,” not the small mind we normally work with but the big mind that we share with others, all buddhas of the ten directions. And as it is said, “when the mind rests on nothing (which is to say, when we are not attached to our thinking), then True Mind arises.”

CODA: STORMS AND CICADAS

Early Saturday morning we met in the dojo just before a severe thunderstorm kicked up. As it approached, the leaves in the trees began to shiver, and then the trunks of the trees began to sway, as the hard rain fell and the wind blew. First the birds shut down their performances, then the frogs. The cicadas would not come out until later in the day, after the storm passed. After the storm calmed down a little, the Abbot began to speak, but rolling thunder continued to punctuate his talk, like the sound effects of some Gothic movie.

Well, that was an excellent demonstration of how the man of no rank sits peacefully in ku. In this square meter where each of us sits on our zabutons, within the dojo or the grass hut, the whole universe arises. The storm outside (shiki) rages on, while the man of no rank sits inside (ku). The moon is contained in a dewdrop, the storm is contained inside your skull… It resonates there but it does no damage.

This is how we can approach the storms in our lives, allowing them to pass [thunder] without letting them disturb us. Because ku or emptiness is no different from shiki, phenomena; peacefulness is no different from the storm’s rage, no different from our anger, our passion. This is what is so difficult to understand — nonduality: samsara (the cycle of peace and suffering, birth-death-rebirth) is not different from nirvana (extinction). As long as we insist on separating them, we will be troubled, rejecting one in favor of the other, pulling weeds to let the flowers grow, which is no better than pulling up the flowers to let the weeds grow. Preferences! Preferences kill zazen.

The role of Buddhism, as you know, is to relieve suffering, to help us in this life, here and now, not to worry about the next life, if there is one, in the hereafter. Not just our own suffering, but that of others, as well.

The goal of Zen, of course, is the goal of no goal. But the goal of no goal serves that same purpose, unconsciously, automatically, naturally.

When you leave here, whenever you’re troubled, remember the grass hut. Remember the original master within.

Long before I began to practice Zen, I remember driving one morning just after dawn through some foggy pastures in Tillamook, Oregon. There was a thick mist on the ground, a bright shining cloud about three feet high on the ground. Cows were grazing there, but they looked like ships floating in the clouds, their heads dipping into the clouds and reappearing, chewing knots of grass. It was the most peaceful scene I had ever witnessed. So after that, whenever I was troubled, it became a kind of mantra for me to remind myself: “the cows are grazing in Tillamook.” And it would calm me, and I could get through whatever it was, even the worst of things, the worst of pain, betrayal, failure.

Remember the grass hut, or whatever else it is that serves the same purpose for you.

Perhaps you will remember the cicadas singing. These loud cicadas, which in Chinese mythology, represent reincarnation because of their brief life aboveground and their cyclical return. Or in Greek mythology, how the cicada represents immortality. When the handsome young Trojan Tithonus fell in love with the dawn, Eos, she asked Zeus to give her young lover eternal life, which he did. However, even Zeus could not give Tithonus eternal youth, and he wasted away until Eos took pity on him and turned him into a cicada so that he could shed his brittle shell periodically (every thirteen or seventeen years, the age of pubescence) and fly off with a fresh body of new life.

Perhaps someday you will say, “the cicadas are singing in Sewanee.”

I am reminded of Robert’s last years when, after a long life full of vitality (his bodhisattva name given to him by Deshimaru, after all, means Spiritual Vivacity), he wasted away to a desiccated shell of his former self. I remember thinking of him as a kind of Tithonus in the flesh, specifically that of Tennyson’s poem “Tithonus,” “A white-haired shadow roaming like a dream.” As the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite tells us:

...when loathsome old age pressed full upon him, and he could not move nor lift his limbs, this seemed to [Eos] in her heart the best counsel: she laid him in a room and put to the shining doors. There he babbles endlessly, and no more has strength at all, such as once he had in his supple limbs.

In later versions, Eos turns Tithonus into a cicada, living eternally, but eternally screeching for the easeful death that will never come.

Would it be too much to suggest a parallel with Dogen’s shin jin datsu raku — “throw down” or “slough off” body and mind during zazen? It seems to be no accident that in Mandarin Chinese “cicada” and “Chan” (Zen) are pronounced the same and even have similar kanji.

The poet Basho’s cicada is very different than that of the Greeks, being mortal but singing seemingly without consciousness of its mortality, because now in the full flower of its life it perhaps has no inkling of its coming death:

The cry of the cicada

Gives us no sign

That presently it will die.

Baso’s cicada represents not old age and suffering, nor even metamorphosis and reincarnation, but rather a literally vibrant present, the present of sexual mating and reproduction, the continuance of life, about to leave its exuvial shell, its skin-bag, behind like an empty hut.

[Rolling thunder.]

Eno (Huineng) (638-713), the Sixth Patriarch of Zen, his mummified and lacquered corpse, Nanhua Monastery, Shaoguan in Guangdong Province