Richard Reishin Collins, Abbot

Kusen, Stone Nest Dojo, 19 May 2024

Yesterday, as I was reading in my study, I heard a thump against the glass of the outside doors. When I looked to see what had caused the noise, I saw a bird twitching on the bricks, but it didn’t twitch for long. It was a yellow-billed cuckoo, its long tail-feathers beautifully dappled, as though a painter had taken pains with each stroke. It was still warm with recent life and pliant, draped across my palm, head hanging down, and its white breast was plush and soft and still, its eyes black as glass beads and dead.

Sometimes we get caught up in the quality of our zazen. We want to make sure we are doing it right. If we have a bad day, if we are uncomfortable in body or mind, we wonder what we are doing wrong, how to make it better. But this is unnecessary, mistaken. Yes, we can make small adjustments, get our knees on the floor, make sure our butt is high enough on the zafu to assist the curvature of the lower spine, bring our shoulders back but not too far back so that our posture is erect, draw the collarbone up and the chin in, and stretch the backbone so that our head presses the sky.

But there the need for assessment ends. The focus need not be so inward or critical.

Every zazen is unique, you have heard me say it before. Every time we enter the dojo, the dojo is not the same as it was last time, and neither are we. It is warm and humid today, sunny after recent rain, and the windows are cranked open to let in the breeze (if there were a breeze) and the songs of the birds in the trees and the cicadas vibrating everywhere. But next time we meet here in the dojo there will be rain, or the trees will be bare, or it will be cold, or the birds will be on vacation or on strike, keeping their song to themselves, the cicadas done with their mating cycle and gone back to their underground lairs.

And next time we meet we will be different, too. As Heraclitus said, we can never step into the same river twice. Another way to say this is, the same person never steps into the river twice.

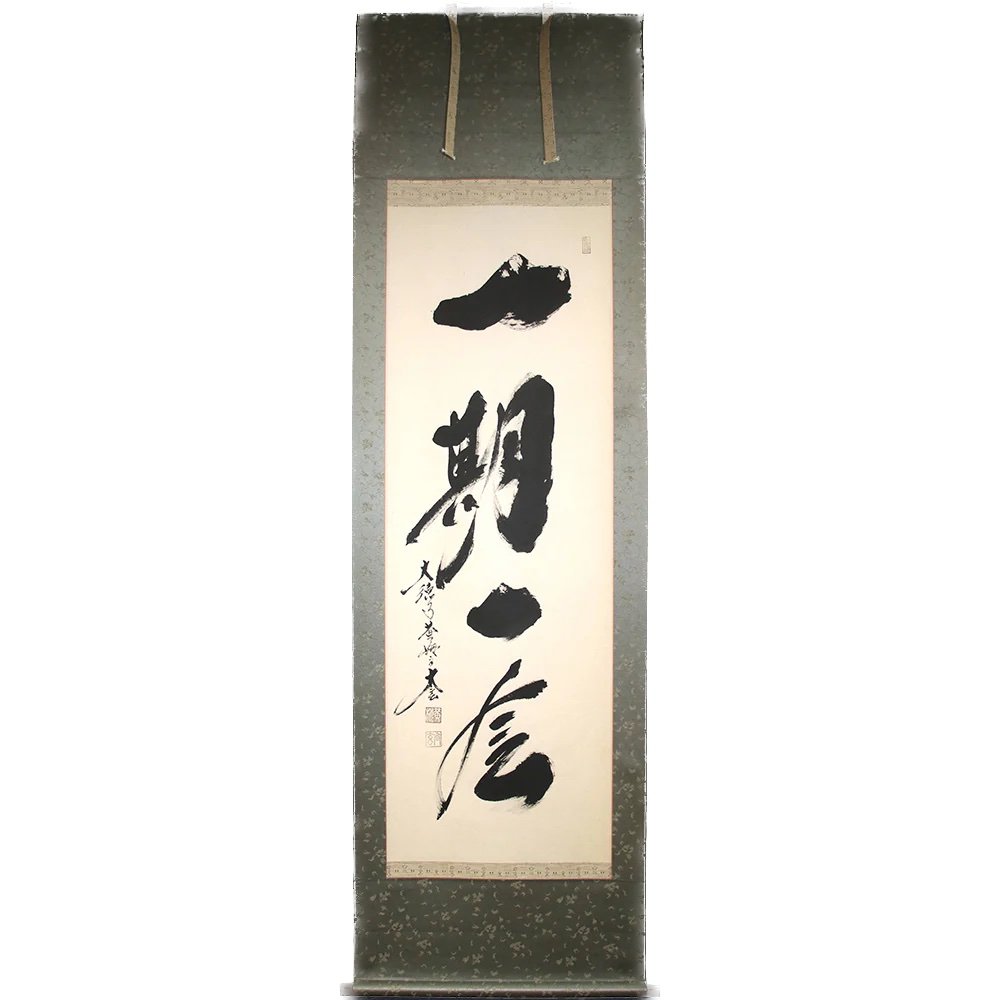

Ichi-go, ichi-e. This common calligraphy phrase found on so many Japanese tea scrolls means that we have one chance to make the most of our one meeting, whether this meeting is with another person, with the natural wonders, or with ourselves. How do we make meaning of our lives in the moment? How do we grasp the richness available to us in the chance of our one meeting, the one chance meeting that is the here and now? Not the one chance “of a lifetime” that is Frost’s road taken or not, I am not talking about that kind of moment, but rather the moment that comes to us in each moment, the moment we can grasp in its suchness, what is called the tathata: the ultimate inexpressible nature of things. This meeting is, after all, what Dogen meant when he set out to find the rationale for practice in light of the fact that we are all, after all, already enlightened. We all have the enlightenment experience available to us at every moment of every day of our unrepeatable (and inexpressible) experience of ichi-go, ichi-e. Do we pay attention through practice, through zazen, through grasping the chance? Or do we go on our way without giving our cuckoo lives our full attention?

It reminds me of Auden’s poem “Musee des Beaux Arts,” where he views the painting by Breughel in which Icarus has fallen from the sky into the bay where merchant ships go on their way, and even if they bother to look they won’t be able to see “something amazing,” a boy falling from the sky or what the significance of that wonder might be, since they are too preoccupied by the habits of their unconscious day, like the dogs who go on with their doggy lives.

If not for zazen, I might have been like those sailors on the merchant ships and ignored the yellow-billed cuckoo that swooped down from the sky and knocked at my door.

And yet this was a perfect example of ichi-go, ichi-e, one chance, one meeting, a moment to make some sense of our life. At least until we too take a wrong turn, or mistake a mirror for a window, or a window for a doorway, or a doorway for a way out. Until we throw ourselves against an invisible wall that we don’t see coming until it is too late. Until mujo strikes, or until we strike mujo.

Oh, but the beauty of the yellow-billed cuckoo!

Ichi-go Ichi-e